News & Media > Editorials > Exposing the pork industry's biggest secret

Exposing the pork industry's biggest secret

In early 2023, our investigators captured footage from inside Victoria's three largest pig slaughterhouses.

This is the story of how we did it and why we won't stop.

For many of us, the discovery that pigs are paralysed inside industrial gas chambers was a sickening one. While the death of any animal in a commercial context is brutal and unnecessary, there is something horribly evil about a machine that lowers pigs, who have a level of intelligence akin to a 3-year old child, into a chamber filled with Co2 gas, causing them to painfully gasp for air, spasming and screaming until they eventually fall unconscious.

These chambers were exposed for the first time nine years ago in 2014, when investigators from Farm Transparency Project (then Aussie Farms) investigated their use at Corowa abattoir in NSW which was, at the time, the biggest of its kind in the southern hemisphere. For those involved, there was a certain, perhaps naive, hope that once something so horrific, so undeniably evil was exposed, change would have to happen.

Instead, the director of FTP Chris Delforce was raided and charged for the footage, with police entering his home and seizing his belongings. Since then, gas chambers have been exposed all over the world while the industry itself has gotten better at making them more efficient, larger and more protected from those who seek to shine a light on what happens behind the heavy metal doors of these brutal machines.

So, when we decided to revisit these chambers to get new footage, we knew that we would have to go further than we had before.

Benalla Abattoir, Northern Victoria

The first slaughterhouse we went to was in a rural area, surrounded by forest, paddocks and trees. We spent two weeks there, installing cameras, documenting the lives of the pigs waiting for slaughter and learning as much as we could about the chambers so we could inform the public about how they operate and what the pigs experience inside of them. We squeezed our way inside, climbing down the slippery maintenance ladder on multiple occasions to retrieve cameras but also to understand the effects of the CO2 gas which was still present even though the machine was switched off and gas was not being pumped in.

The first of us who went down didn’t even make it to the bottom before she had to scramble back up, shaking, gasping and almost unable to climb to safety. The feeling of panic induced by sudden and overwhelming ‘air hunger’ is primal and almost impossible to push past. After that, we would hold our breaths when climbing into the chamber, yet we’d still experience burning eyes, lightheadedness and chest pain due to both a lack of oxygen and the gas itself, which always found a way into our lungs and heads.

It was at this slaughterhouse that we got footage of piglets being herded into the chamber and gassed to death. We spent time with them the night before they were killed, sitting in their pen as they nuzzled us and cheekily tried to chew our shoelaces, torches and clothes. Later, we watched them die inside the chamber in footage from our hidden cameras before seeing their tiny bodies hung up and numbered in the chiller room. We couldn't save any of them, comforting ourselves only with the reassurance that we would do whatever it took to tell their story.

Thanks to new advances in hidden camera technology, our footage from this slaughterhouse was higher quality than any in existence. It showed the pigs suffering and it told their story. But we knew we could do better. That’s when we started to plan.

While working on getting footage from another slaughterhouse, we realised that, although we had only planned to install one camera at that location, it provided the perfect opportunity to do something bold. Although there are workers all around these chambers to push the pigs through the race and pull them out at the other side, every pig sent inside a gondola dies in darkness, with no one living to witness their final moments. We wanted to change that. Installing cameras was no longer enough, so we decided to install an investigator.

Australian Food Group Abattoir (AFG), Laverton

We’d be lying if we said that putting an investigator inside a gas chamber to film the final moments of pigs wasn’t what we planned all along. How it happened though and the speed with which it occurred was unexpected.

After coming to the realisation that this plan may actually be possible, we spent a frantic three days doing as much research as we could. We needed to know if someone could remain hidden for long enough to film inside the chamber. We spent hours watching back old footage taken from inside the facility, as well as footage from our cameras installed that week. We knew that a heavy, rubber screen blocked the view into the chamber from the workers who pulled the pigs out and slit their throats, while the low, narrow door through which pigs were forced into the gondola, often with boots and paddles, was too low down to easily see through. As in many cases, the measures taken to ensure that as few people as possible could see what happens inside these chambers was exactly what allowed us to capture it.

On the night we went in, two investigators entered the facility. Only one left.

Chris spent 9 hours and 20 minutes inside that gas chamber, inches away from discovery the whole time. He watched and recorded hundreds of pigs being killed over three hours, witnessing their agony and looking into their eyes as they pleaded for mercy. We had thought that workers would rarely enter the chamber and, if it was operating normally, they wouldn’t have. Yet malfunctioning machinery and the many times pigs got stuck in the gondola, unable to be tipped out meant that workers were often looking inside and, at one point, even climbing on top of the gondola directly below where Chris was hiding.

While Chris hid inside, a small team waited down the road, anxiously waiting for any word and keeping tabs on any activity. The waiting was tense with both people in the car constantly checking their phones, breathing a sigh of relief any time a message came through and feeling their fear grow as the minutes ticked by without news.

From our investigation we knew that there was a window of opportunity for Chris to leave the chamber and get out without being seen or stopped. When that time finally rolled around, his team outside flew a drone over the facility, watching for any workers who might stop him on his way out. Watching the birds-eye view, we saw as Chris exited, walking out in a high-vis outfit similar to that worn by the drivers who dropped pigs off in trucks. The triumph of achieving what we intended to do was mixed with despair as we watched the footage and Chris recounted the experience of being almost face to face with these intelligent, feeling animals as they breathed their last; fighting right up until the end. Even after doing this work for 12 years, upon leaving the chamber he said that it was undoubtedly the most horrible thing he has ever seen.

Diamond Valley Pork (DVP), Laverton

After getting handheld footage from inside AFG, we knew that we had to get the story out there as soon as we could. What we had was too powerful to hold back and we also felt that we owed it to the pigs whose deaths we witnessed to tell their stories, but there was one missing piece of the puzzle.

Diamond Valley Pork is the largest pig slaughterhouse in Victoria. A sprawling set of gunmetal grey buildings in the suburb of Laverton, 17km out of Melbourne, DVP slaughters up to one million pigs every year, 20% of the nation’s total. In 2015, Animal Liberation Victoria and Animal Liberation NSW captured footage inside the gas chambers at DVP, as part of their ‘Pig Truth’ campaign, and locked on inside in response to the horrific sight of pigs' agonising final moments. DVP retaliated by increasing their on-site security, installing more cameras and hiring a guard to patrol the facility so that there was never a moment where anyone could see what happens behind the forbidding walls. Yet, the sounds of pigs screaming could still be heard at all hours of the day as they were locked in concrete holding pens and forced up a narrow corridor to a painful, violent death. We knew that we couldn’t tell the full story of pig slaughter in Australia until we got inside and installed our hidden cameras in the biggest, most sophisticated gas chamber in the state.

For months we thought of getting into DVP as an impossible task. Jokingly nicknaming it Siberia in reference to its cold and hostile atmosphere, we spent many nights parked just streets away from the facility, surveilling it and looking for any way in. Hours were spent poring over photos until we found it. Our window of opportunity.

For one hour, every week, there was a gap between when security left in the early hours of the morning and when workers arrived. We’d found our way in. But now the true challenge began as we started an investigation which was characterised by a constantly ticking clock and the heart pounding knowledge that at any moment we could be caught, our footage taken and everything we’d done up until that point prevented from ever being seen.

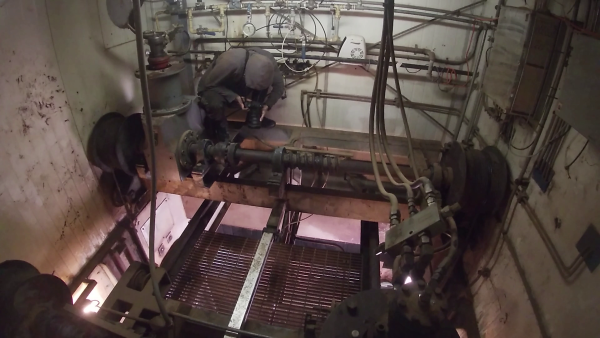

DVP is the first gas chamber in Victoria to be built with the new ‘backloader’ design, which is becoming the norm for large pig slaughterhouses around the world. In these chambers, designed by food processing company Marel, pigs are pushed up a ‘race’ using mechanised walls which close in on them, eventually forcing up to 8 at a time into enormous, metal gondolas. Inside the chamber, five of these gondolas rotate, lowering pigs into the suffocating gas and tipping them out the other side, all completely out of view of workers and supervisors. From the outside, you would have no idea of the purpose of this machine, as it is enclosed on all sides by metal walls with not even a window to see inside. The only evidence of its purpose is a thin white pipe which snakes along the side, carbon dioxide written on it in black.

In our small window of time we installed cameras directly inside the gas chamber, each time sprinting out with only minutes to spare. One night an investigator dropped a tube of glue directly inside the gondola and we spent a heart pounding 20 minutes trying to retrieve it, knowing that if we couldn’t, our entire investigation would be over. In the end, one of our team forced herself down the narrow gap between the chamber and the wall, managing to lift the glue out with pliers but almost becoming stuck in the process.

With each night and each new risk taken, we felt an increasing sense of urgency to get the footage out there while we still could. However being restricted to only entering once a week was holding us back. We tried other times, donning high vis and attempting to enter while workers were on site, only to hurriedly leave when someone was spotted unpacking boxes directly opposite a door just as an investigator was standing outside of it, gesturing for others to join her. We tried again on another night, determined to install more cameras. This time an investigator opened a door into the kill room only to hurriedly leave as he spotted someone inside cleaning, just metres away.

Still, we persisted, and managed to retrieve footage of pigs screaming in agony inside this chamber, their deaths just as violent as the other two places we had been to. This footage, the first in Australia inside these newly designed backloader chambers and the first from inside this facility in eight years, gave us exactly what we needed to tell this story. It showed that almost a decade after Australian investigators first filmed what really happens to pigs inside these chambers, they are still just as brutal, just as violent, just as painful and just as horrific. They also told us one more thing. Exposing these chambers for the first time hadn’t made the pork industry act or made them do anything to improve the lives of these pigs. All it had done was to make them and the facilities they represent more secretive than ever. This secrecy is what we fought against and yet, ironically, it was the very thing that allowed us to do what we did, installing cameras and even investigators directly inside these sinister machines to witness what is hidden from sight.

The role of investigations is to document and expose the reality of animal use and exploitation. Using technology we tell the stories of animals who otherwise would be known only as a number on an ear tag or a product on a shelf. Much of the animal welfare ‘progress’ that this country is so proud of, wouldn’t have happened without the work of animal advocates who risked their safety, and sometimes their lives, to show consumers what the industry would rather keep hidden. When you’re inside a slaughterhouse though or watching back the footage of animals being violently killed, it doesn’t take long to realise that improvements to welfare do little to soften the fact that all animals want to live and that all of them fight to survive until their very last breath.

We will not stop exposing the dark truths of these industries and we will not stop fighting until all animals can live freely and with dignity.