News & Media > Editorials > The Life of a Christmas Turkey

The Life of a Christmas Turkey

Turkeys are affectionate, playful, and intelligent birds, who form strong bonds with their flock mates and recognise the faces of their friends (human and turkey alike). Turkeys bred into the animal agriculture industry suffer immensely, from breeding to slaughter and all practices in between. In Australia alone, approximately 6 million turkeys are slaughtered for their flesh every year, and roughly 4.5 million of these are consumed at Christmas.

At a time of year when love, unity, and kindness are at the forefront of our hearts and minds, it is a fitting time to give consideration to how our actions can make the world a kinder place for turkeys.

Breeding

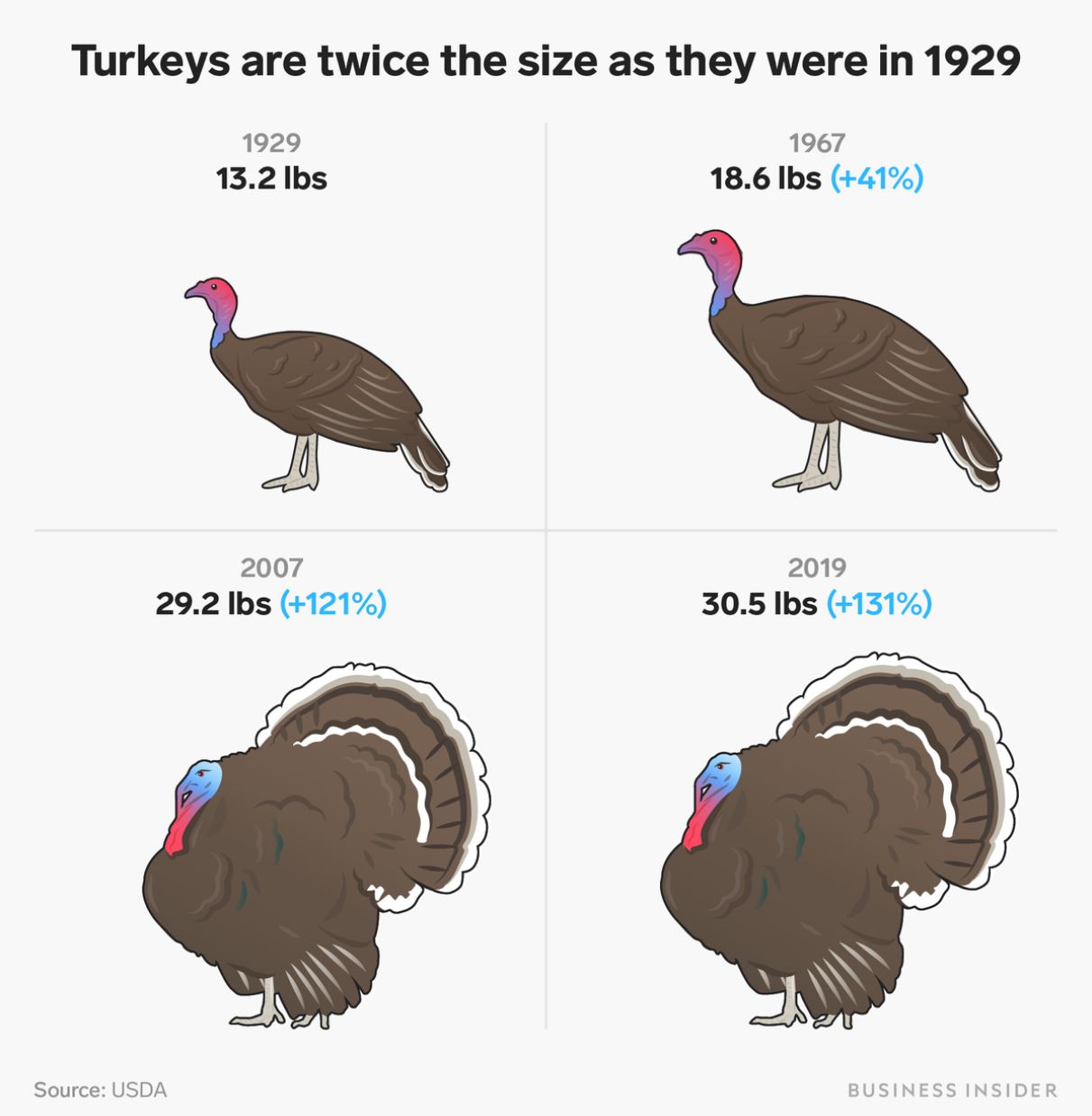

Turkeys used for breeding are kept in parent bird sheds. These large barren sheds have no enrichment - turkeys have little room to move around, stretch their wings or dust bathe and they are never afforded access to the outside world. Turkeys often live among the remains of deceased birds whose bodies could simply no longer go on, as well as their own excrement that builds up over their time in the shed. Genetic manipulation through selective breeding means turkeys grow at an accelerated pace to almost double the size they would have in the 1960s; consequently, turkeys bred for commercial use are unable to breed naturally and instead the process of artificial breeding is used.

This process involves collecting semen from male turkeys (toms), a process also referred to as ‘milking’. The semen is collected by restraining the tom and masturbating the turkey until they ejaculate and the semen can be collected. A small plastic straw is often used by operators to collect the semen, sucking it into the straw with their mouth.

The next step in this exploitative process involves injecting the female turkey (hen) with the semen. Like the semen collection, the hen is restrained; pressure is applied to her abdomen, pushing out her cloaca (a turkey's reproductive organ), and the semen is injected into her whilst the pressure is simultaneously released from her abdomen.

The artificial insemination process is repeated weekly over the course of a year. Once turkeys have been breeding for one year, their production begins to slow and thus their economic value is diminished, so they are sent to slaughter, to be replaced by younger turkeys to repeat the cycle again.

Bestiality is a criminal offence under the Crimes Act 1958, but these laws don't apply when undertaken for agricultural and vivisection purposes, which is just one of a myriad of examples of laws failing animals.

The Hatchery

The life of a Christmas turkey begins at the hatchery. A hatchery is where eggs of poultry are hatched through artificial conditions. Once hatched, the turkeys are mutilated before they are boxed up and delivered to farms to be grown out for slaughter.

Debeaking and declawing are two standard practices undergone in the turkey meat industry. Due to living in crowded confinement, turkeys can become aggressive, and cannibalism and peck injury are common responses to intense boredom. Debeaking is the removal of one-third of the top of a turkey's beak. The most common way to do this is by use of an automated carousel which restrains the head of the turkey poults and applies an infrared laser to the beak, damaging the tissue and causing it to gradually die and fall off over two weeks. Another common method is the use of a hot blade to cut off the tip of the beak.

.jpg)

Toe-trimming is the removal of the end of turkeys' toes to stop their claws from re-growing - this is done by restraining turkeys by their legs and applying microwave energy to the ends of their toes.

These procedures are ultimately undertaken to ensure carcass quality isn’t decreased by turkeys injuring one another whilst confined together, it has nothing to do with the welfare of these animals, because if their welfare was truly considered they would not be living in such a manner that requires them to have these procedures done in the first place.

Both debeaking and declawing have been described as acutely painful, and studies have shown turkeys experience ongoing pain following the procedure.

On the farm

Turkeys are housed in intensive farming sheds, with stocking densities set at 46kg per square metre. Up to 20,000 birds can be housed in a typical shed 153m long and 15.3m wide. Artificial light is used to distort turkeys' eating and sleeping patterns in order to promote faster physical growth.

Turkeys live on the same litter for the entirety of their lives up until they are slaughtered, meaning they live on their own excrement and urine for up to 17 weeks. Build-up of urine causes ammonia in the air; investigators have testified to the burning they experience in their eyes and their nose when entering a turkey shed. It is hard to imagine what it might be like for turkeys living in such conditions for their entire lives.

The contact with soiled litter can cause burns to their bodies, with many turkeys developing a condition called footpad dermatosis, a painful condition that sees birds' feet become cracked and swollen. Research has suggested that it is impossible for a flock to have no cases of FPD in intensively farmed sheds.

Due to turkeys being selectively bred to grow to unnatural sizes, they experience a number of health problems, most commonly leg issues. Turkeys' legs often begin to give out, unable to support the weight of their oversized bodies, and many begin to have trouble walking until they eventually can't. For these turkeys, their death is slow and painful - unable to reach food or water, they starve to death, their skin developing urine burns from the ground they lay on.

Slaughter

The end of a Christmas turkey's life of suffering is one filled with fear and pain. The two most common methods of slaughtering turkeys in Australia are bleeding cones and the shackle line with electrical stunning.

Bleeding cones are funnel-shaped metal apparatuses, in which turkeys are placed upside-down, their heads and necks exposed at the bottom of the cone whilst the rest of their body is restrained inside. The slaughter person takes the head of the turkey in one hand and holds it firmly whilst using their other hand to decapitate the turkey. Their bodies bleed out in the cones, and they are then removed and processed. Some turkeys’ bodies convulse so hard that they fall out of the cones.

In a recent investigation into Numurkah Turkey Supplies in Victoria, where both the killing cones and electrical stunning method are used, turkeys are seen in holding pens witnessing the turkeys before them being beheaded in the cones or shackled by their feet. The Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals (Domestic Poultry 4th Edition) states that ‘care must be exercised to ensure that poultry are not subjected to unnecessary stress while awaiting slaughter’. It is difficult to understand what care is being taken at all when turkeys are witnessing their flock mates being decapitated, their bodies thrashing around and falling out of the cones before they themselves suffer the same fate.

The most common means of killing poultry – including turkeys – is the shackle line with an electrical water-bath. Turkeys are shackled upside-down by their legs, their heads pulled through a bath of electrified water intended to render them unconscious, before their throats are cut or they are decapitated. A number of investigations have revealed the frequency in which poultry lift their heads, avoiding the stun bath entirely, and thus having their throats cut or being decapitated whilst fully conscious. That is not to say that if animals are properly stunned every time it becomes morally acceptable to kill them, but rather shows that these ‘errors’ are symptomatic of an industry profiting off the exploitation of animals. Animals, unlike machines, move at their own volition - they can be unpredictable and won't always do what someone wants of them. As long as animals are being forced into situations they do not want to be in, they will struggle, and there will always be errors.

The recent investigation into Numurkah Turkey Supplies has also revealed that turkeys' wings frequently make contact with the live water before their heads, delivering extremely painful electric shocks. The national Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals Livestock at Slaughtering Establishments states that ‘In using the method of stunning which involves immersion of the head and neck in electrified water baths, care should be taken to ensure the wings do not touch the water first’. The Victorian code, however, does not explicitly mention this.

The life of the Christmas turkey is one filled with pain, misery, and suffering from the time of their hatching, to the time they are slaughtered. Turkeys are beautiful creatures - anyone who has had the opportunity to get to know them would see they are loving, affectionate animals much like the dogs and cats we share our homes with. This Christmas, you have the power to help create a kinder world for turkeys, by leaving them off your plate.

Farm Transparency Project

Farm Transparency Project