News & Media > Editorials > Is Veganism Only About Animals?

Is Veganism Only About Animals?

The history of veganism

In answering the question, ‘is veganism only about animals’, we should first consider the history of veganism. People have chosen to eat plants and avoid all consumption and wearing of animals far back into history. In ancient India, people like the Buddhist emperor Ashoka advocated for animals and their wellbeing. Ashoka, who lived as far back as 304-232 BCE, set out laws that protected animals from slaughter and hunting. These laws were based upon the principle of ‘ahimsa’, or non-violence. Even earlier, about 1500 BCE, Buddhist scriptures referring to ‘ahimsa’ stated that ‘without doing injury to living things, flesh cannot be had… hence eating of flesh should be avoided’. They further proclaimed, ‘do not injure the beings living on the earth, in the air and in the water’.

These ideas of non-violence later crossed borders and were further explored in Ancient Greece. Pythagoras described meat as the ‘sad flesh of the murdered beast’. Then, in the Romantic Era of the 1800s, authors wrote about animal rights, as well as issues of class and human rights, and how these intersected. Eating animals was considered to be something the wealthy did at the expense of those who were poorer, because animal agriculture is so inefficient, feeding less mouths than if we ate plant foods. At the time, people who were vegan called themselves ‘strict vegetarians’.

Pythagoras advocating vegetarianism. 1618-1620, Peter Paul Rubens.

Defining veganism

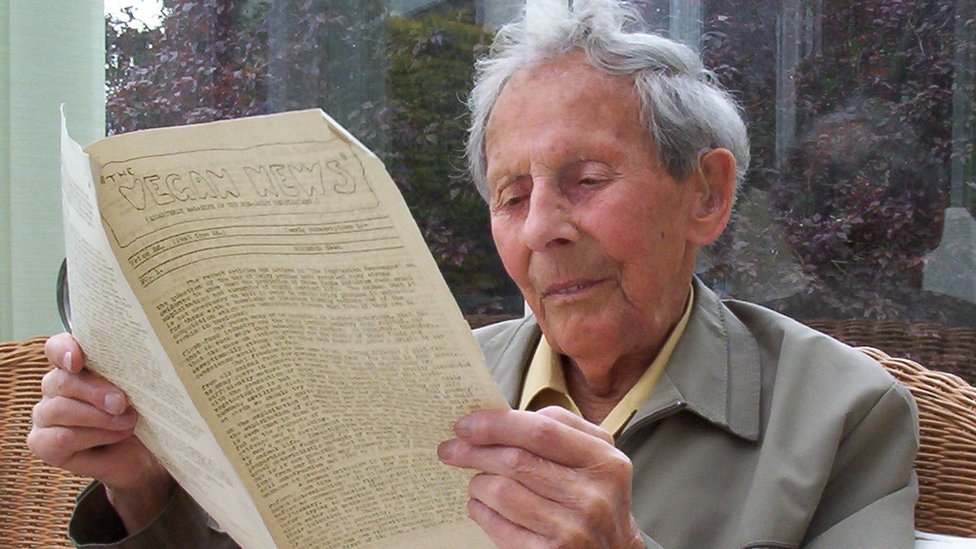

The same principles that underpin modern day veganism have been around far longer than many of us may realise. Yet, the word ‘vegan’ itself, was coined by Vegan Society founders Donald and Dorothy Watson in only 1944. When Watson and the Vegan Society created the word, they came to a definition for veganism which follows:

‘...a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose; and by extension, promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans, animals and the environment. In dietary terms it denotes the practice of dispensing with all products derived wholly or partly from animals.’

Some things in this definition are likely unsurprising to most vegans. Veganism is about more than a plant-based diet. Veganism is broader than diet, because it is about the avoidance of all animal exploitation and suffering. Suffering that comes from puppy farming, wool wearing, cosmetics testing, horse racing, and so on.

Perhaps more surprisingly to some, is that the definition of veganism and who it should benefit extends beyond non-human animals, too. The environment and humans can benefit from veganism, and this benefit is definitively important to veganism as a principle of non-violence.

Donald Watson of the Vegan Society.

Why it makes sense for veganism to be for animals, as well as humans and the environment

At the moment in some animal rights circles there are discussions around veganism being ‘hijacked’ by human rights issues. Activists, even those with good intentions, fear what this means for animals who are so oppressed.

It’s important to note that certainly, animals deserve their own movement of people who focus on their liberation. However, looking at how animal suffering interacts with human suffering is not ‘ruining the movement’, but actually critical to total animal liberation, effective activism, and the march toward a totally just world.

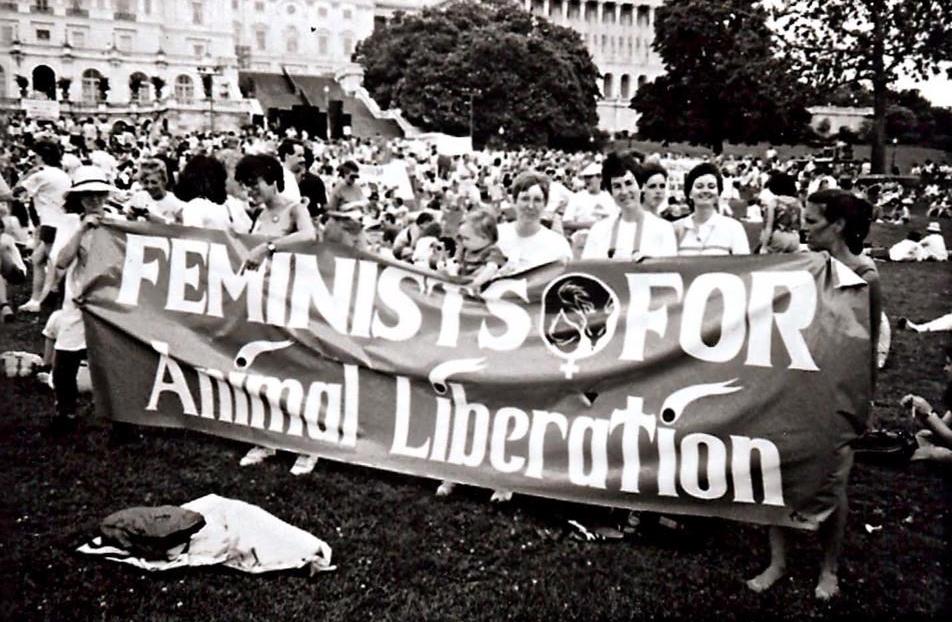

Being concerned with both human and animal rights simply makes sense – you cannot truly be against oppression if this is only the case sometimes. Being opposed to oppression should be an all-encompassing thing. More specially though, there are plenty of ways in which the suffering of non-human animals is deeply interwoven with the suffering of humans. Not two separate issues to address, but one system of violence and harm which hurts us both, us all.

'Feminists for Animal Liberation'

How animal and human rights intertwine within animal exploitation industries

People who work in slaughterhouses are prime examples of the complexity of oppression and violence in society. Slaughterhouse workers commit horrific violence. They spend every working day killing animals. Hundreds, thousands each day. There is no justice inside slaughterhouses, only frightened animals, running blood, corpses.

While it can be easy to cast people working in slaughterhouses as the enemy of animals, the world is more complex, the issue more nuanced. For starters, people who work in slaughterhouses are fulfilling a desire of the public - they may be closer to the violence, but no more complicit than the average consumer of meat, dairy, eggs, wool, leather, and so on. Secondly, these slaughterhouse workers are victims themselves. Somewhat like the animals who are objectified, transformed from living being into neatly wrapped packages of ‘food’, slaughterhouse workers are treated as commodities to create income through.

Slaughterhouse working people are treated exceptionally badly – some reports have found these workers to wear nappies because they are denied access to toilets – they are at great risk of severe injury, and most distressingly, they are very likely to become mentally unwell because of their work. Work which no one would choose unless they had no other choice.

Some activists suggest that there ‘must’ be another choice for people who work in slaughterhouses, implying people really do choose to kill for a living. In reality, in country towns far out from the city, there aren’t toilet cleaning jobs, or the myriad of other unpleasant, but available jobs that can be chosen by people in more populated areas. It is upsetting, but some people don’t have a choice but to work somewhere horrific, doing horrific things to animals, that most of the population pay for.

As a result of their violent work, slaughterhouse workers experience mental health problems, including perpetration-induced traumatic stress, a kind of mental suffering which comes from having committed violence against someone. In turn, this mental ill health is likely tied to disproportionally higher rates of violence, including sexual violence amongst communities near slaughterhouses.

Violence only creates violence, and the way this impacts individuals is complex and devastating. It simply is impossible to say for example, how I may change if I my circumstances forced me to work and commit such traumatising and vicious acts against animals every single day, for a prolonged period of time. I can’t bear the thought of even accidentally harming an animal, but it’s safe to say most slaughterhouse workers didn’t dream of killing animals when they grew up, either. Hurting animals is not our default as humans. It’s important we remember this, and extend this principle to slaughterhouse workers who are suffering, who may desperately want to work in a different industry.

Illustration by Katie Horwich, from the BBC's article, 'Confessions of a slaughterhouse worker'.

How animal rights intertwines with not only human, but environmental rights

Let’s explore another way animal, human and even environmental rights issues intertwine. Deforestation in the Amazon is an ecological disaster; a disaster for the wild animals and indigenous people living on this land. It is a disaster too, for the animals who are bred for slaughter on this cleared land – the primary purpose of the deforestation itself.

We live in a complex world which means that problems are complex, not singular in their issue. Deforestation for example, can be and is an environmental, human, indigenous and animal rights issue. Veganism which considers all these elements, can alleviate a wide range of negative impacts and sufferings. Seeing issues in this collective way is not ‘bad for animals’ or distracting from their plight. Instead, it allows us to see how big this problem is, and so it allows many groups of individuals to work together to uproot a common source of oppression for many – regardless of species.

"Sometimes, when we see the trees cut down, we feel rage," says Guajajara Guardians of the Forest chief Claudio da Silva. "This is why we keep fighting, so this doesn't happen."

Image by Sam Eaton. Brazil, 2018.

On the importance of extending compassion beyond species

This is why extending our circle of compassion is important. This idea of broadening our view of who we care for is one that animal advocates put forward often. We ask humans who are passionate about human social justice issues to extend this care to animals all the time. Rightly so. Sometimes though, we do not do the reverse, and remember to care for humans. We forget that our veganism is rooted in an opposition to violence and oppression. We forget that our veganism is rooted in anti-speciesism, which is concerned for life and wellbeing regardless of species, human or non-human.

This whole idea of extending our compassion perhaps may be far more simplified, if we all remember one thing: we ourselves are animals.

Homo sapiens are simply one animal of a known 8.7 million species here on Earth, 0.01% of life here. If we remember this, remember our animality, we can realise that human issues are animal issues, and animal issues are human issues. By remembering that we are not unique in our life, our sentience, or our capacity to feel and think, we can revolutionise what social justice means, and who it helps. Simply put, without speciesism, everyone in the realm of social justice could remove their barrier of concern and include all animals. Those we destroy the native habitat of, those we farm and slaughter, those we are.

The discomfort of our being animals

This whole idea of humans being animals can be difficult to come to terms with, because there is a discomfort which comes with recognising the ‘animal’ within us. It’s uncomfortable, because as we have forgotten that we are animals, we have created a false sense of superiority above those we consider to be ‘actually’ animals. We have put ourselves at the top of a made-up hierarchy, looking down upon all other species.

The fear in recognising ourselves as animals then, is that we might then lose the rights we have at the top of this hierarchy. This is understandable, because our ‘dehumanising’ of individuals, or of ‘animalising’ them, has been deeply harmful to many humans. The human individuals we (we largely being specifically, white, male, able-bodied people) decide to label ‘sub-human’, or ‘more animal’ are subject to violence and oppression. It is through this process of ‘animalising’ that we see racism, sexism and ableism. All of these forms of discrimination are rooted in dehumanization, which is rooted in speciesism. Black activist and writers Aph Ko and Christopher Sebastian have spoken and written in depth about these issues and how they intertwine.

Aph Ko, via Circles of Compassion: Connecting Issues of Justice

Veganism is for us all, because we are all animals.

Being an animal is not a disadvantage, not an inferiority, but the core of all of us here who are living, thinking and feeling on this planet. When we remember that we are animals, we are more likely to treat other animals with respect. We need not fear what we would lose if we were no longer at the top of a cruel hierarchy, but instead consider what we could all have and share if this hierarchy were to topple. Safety, freedom, justice.

Veganism is concerned with the wellbeing of animals, so let us be concerned with, and advocate for all animals - non-human and human animals. This is what veganism is truly for, liberation and non-violence which benefits everyone.